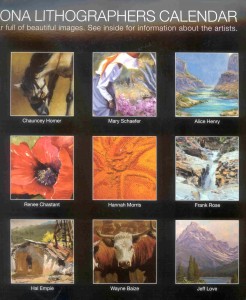

A few days ago I went to Arizona Lithographers and picked up their 2014 calendar. I knew that they included one of my paintings in the calender, but wanted to see it in print. This is part of the back of the calendar with a portion of the August page from a painting I did of Seven Falls in the Catalina Mountains (the painting on the right in the middle row).

Yesterday Ed and I decided to revisit a trail I have hiked many times. It is a section of the Arizona Trail (a trail that goes from Mexico to Utah, a total of about 800 miles.) We drove to Molino Basin in the Catalina Mountains, and set off across the road and toward the east. It was cool with light breezes. This late in November we did not expect to see anything in bloom, but right away we saw several camphorweed plants with a few blooms (Heterotheca subaxillaris). Then one lone wire lettuce (Stephanomeria sp.), and several turpentine bushes (Ericameria laricifolia) loaded with flowers.

The leaves of the Turpentine bush smell like – you guessed it – turpentine.

It took us a while to realize that there was another plant in full and glorious bloom, one of my “invisible” flowers. We were not sure of the exact species, but it is one of the euphorbias, possibly Spurge (Euphorbia pediculifera). The plant was very dry and somewhat shriveled, and it was not until we got home that I could see that it was really in bloom. In fact it was loaded with blossoms, each one very minute.

Here is the plant seen from above

It is about 6 inches across

Here I am holding two little branches of the plant. If you look closely you can see the individual flowers.

This is one flower greatly enlarged (the actual flower is less than a tenth of an inch wide)

There is a lot going on in this tiny flower.

The hillside we climbed is covered with shin daggers (Agave schottii). There were no flowers, but plenty of flower stalks, and some of them sported little baby agaves – pups – plants that were starting to form on the mother ready to drop to the ground and assert their independence. Neither of us had ever noticed shin daggers sprouting babies like this before, though we had seen other agaves that have this skill.

Our turn-around point afforded us a view to the south of Agua caliente hill, and behind it the Rincon mountains. It was a truly gorgeous day, and another delightful hike.